New Hungarian book about Horthy and his effect on history

Krisztián Ungváry discusses Miklós Horthy’s responsibility in the turning events of Hungarian history in his book, and he also conducted a discussion about the topic with his main professional opponent, Sándor Szakály.

The original review of the book and the debate can be found on 24. Whoever writes a book about Miklós Horthy in 2020 automatically enters the political space. For decades after the war, there was no meaningful debate about Horthy, and only a few crossed the political division necessary to assess Horthy’s role since. In the book, Ungváry discusses the specific responsibilities of the governor in the most important historical situations. He repeatedly refers to his career opponent, Sándor Szakály. Jaffa, the book’s publisher, was able to seat the two historians at a table for the book launch, but because of the epidemic, it happened online.

Not all controversial issues could be covered in the debate, but it adds something, and it is becoming increasingly rare for two people with different worldviews to be able to sit down and express their views in a respectful way. Szakály is known to many for his scandalous statements and as the head of the Veritas Történetkutató Intézet (Veritas Historical Research Institute) set up by the Orbán government, but the discussion remained professional. In the end, the parties agreed that the story of Horthy is not black and white, and Szakály even said he would recommend the book to everyone so that they can decide themselves what they think of Horthy.

Ungváry tried to review the specific choices Horthy could have made in the past. This allows for some interesting thoughts as well as sheds light on the weight of Horthy’s decisions.

The full title of the book is: ‘Horthy Miklós – A kormányzó és felelőssége 1920-1944’ (The Governor and His Responsibilities 1920-1944) and will be published on 18 May 2020. Ungváry only deals with contentious cases in which Horthy’s perceived or real responsibility usually comes up. Based on the discussion and the book, let us see what the parties say about Horthy’s political and personal responsibilities.

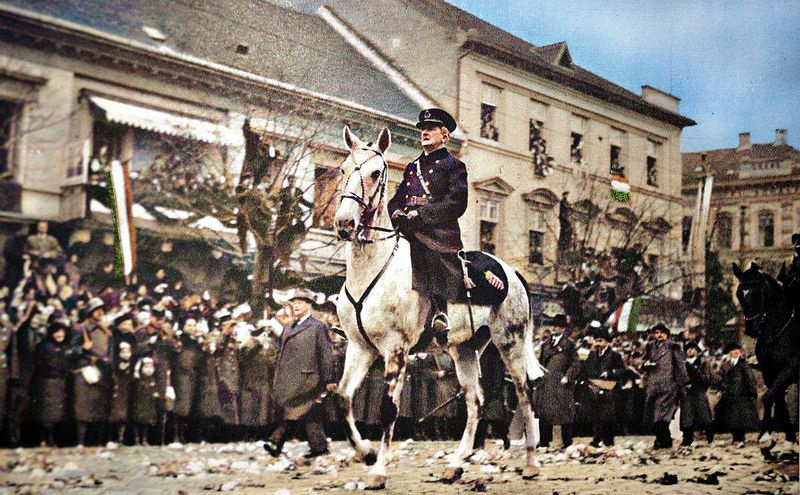

Horthy coming to power and the consolidation

“Viktor Orbán called Horthy an exceptional [sic!] Statesman during the consecration of the Klebelsberg mansion in 2017” because he thought it was Horthy’s merit that “history has not buried us [Hungary and its people] under itself”. Ungváry disputes this on several points. He said Horthy was responsible as an instigator for the white terror that accompanied his rise to power, several of whose perpetrators were later pardoned. Szakály does not fully agree with him.

As for the consolidation, Ungváry acknowledges the success of politics but questions Miklós Horthy’s personal role. According to the book, it was in Horthy’s favour that, standing by Bethlen, he supported the exclusion of Gyula Gömbös and his radical racist followers from the ruling party, but he did not have much influence on the country’s affairs. He remained passive, and only because of the global economic crisis did he re-engage more in public affairs. According to Ungváry, Horthy was easily swayed, and it was merely historical luck to have been influenced by Bethlen.

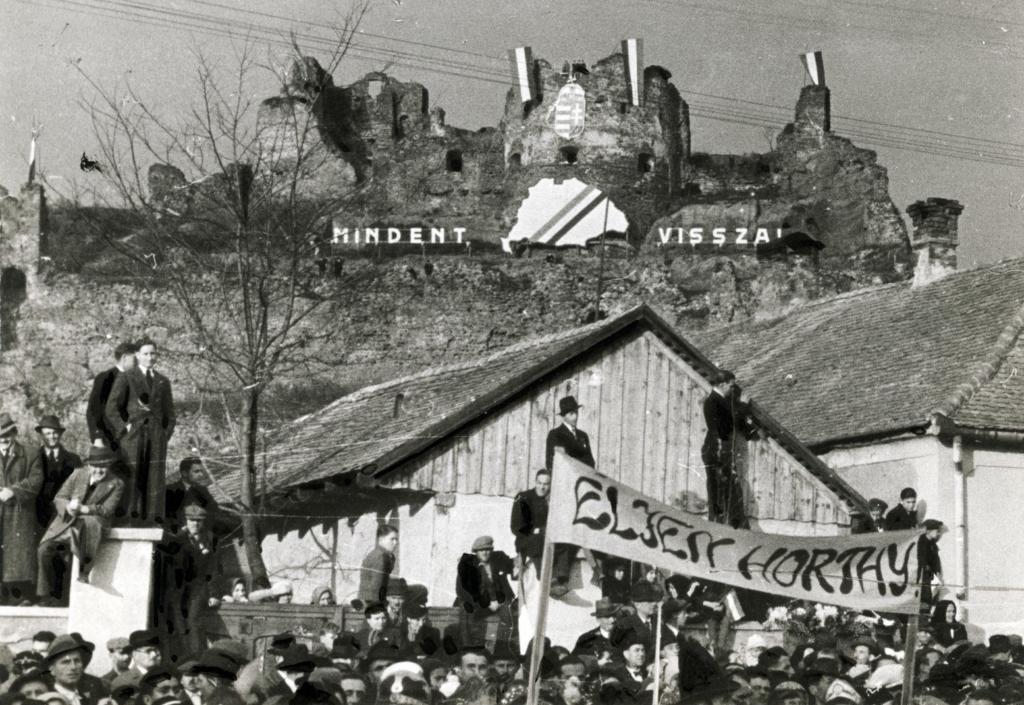

Horthy and the revision

Horthy’s foreign policy goals were openly guided by the revision of the Treaty of Trianon, and this proved temporarily successful, as most of the Hungarian-inhabited areas were returned to Hungary by the Vienna Arbitrations. According to Szakály, this could only be achieved with the help of the axis, and because of this, the country was on a forced path. Ungváry argues in his book that Horthy was not a responsible statesman when he linked the issue of revision to the success of Hitler’s and Mussolini’s fate.

Horthy made a mistake in that he let the ‘everything back’ principle dominate Hungarian politics. Horthy acted as if the restoration of millennial borders had become a reality, as opposed to a more limited, ethnic revision, the legitimacy of which was even recognised by the British.

According to Ungváry, this was reflected in the fact that when Czechoslovakia offered Hungary the Hungarian-inhabited highlands, which was 80% identical to the area later returned by the Vienna Arbitration, Horthy rejected the offer and left the decision to the German-Italian arbitral tribunal. According to Ungváry, due to this greed, no agreement was reached. The governor also pursued other unrealisable dreams: he formed claims for the port of Fiume (Rijeka). To get the port, he would have had a conflict with an allied country for a city with little Hungarian population. Ungváry thinks this shows that Horthy as a politician was not aware of reality, and the author thinks Horthy chased his prime minister, Pál Teleki, into suicide.

Horthy and the war

According to Ungváry, the author of the book, the real sin of the governor was entering the war. With this, he made a permanent commitment to the Germans, even though Horthy was aware that Hitler could not win in the long run. Horthy was blinded by the initial success of the Wehrmacht, and when Germany attacked the Soviet Union, Hungary joined only after a short hesitation. This was the biggest dispute between Ungváry and Szakály. According to the former, Horthy decided to go to war after the bombing of Kassa (Košice) practically on an emotional basis. According to Szakály, however, it was not Horthy who decided. The Bárdossy government declared entering the war after the bombing of Kassa. In 1941, public opinion in Hungary clearly supported entering the war to protect the territories returned by the revision. By then, the Romanians and Slovaks were warring parties, so there was a danger that the Germans would support their demands against neutral Hungary. According to Ungváry, Horthy had more subtle choices; there was no need for military action, which is not an excuse for the fact that there was a German-friendly predominance in the government and the army. Not long after, Horthy ousted his pro-German ministers, which Ungváry thinks showed that the governor later saw he made a mistake listening to them.

Horthy and the attempt at escaping

The least debated issue between the two historians was this one. Ungváry and Szakály both believe that Horthy had personal responsibility for the ill-prepared attempt to escape in October 1944. Horthy gave conflicting instructions, and several of the military officers he had previously appointed failed. According to Ungváry, the following story also indicates Horthy’s attitude when the commander of the bodyguards, Károly Lázár, confronted the governor that several of his generals had lied to him:

Horthy suddenly turned to face Lázár and, outraged, replied, “Generals? To the Supreme Warlord? It can’t be!” He then saluted, said “Adieu”, and left.

Ungváry says it is incomprehensible why Horthy allowed his son, Miklós Horthy Jr., to negotiate with Yugoslav envoys when it was obvious that an agreement had to be reached with the Soviets. The action was a ruse by the Germans. From the time the governor’s son fell into the hands of the Germans, the fate of the escape was sealed. In the book, Ungváry draws a parallel between Marshal Mannerheim, who led the successful Finnish escape, and Horthy, in favour of the Marshal.

Horthy and his relationship with the Jews

Ungváry says that Horthy’s anti-Semitism was clear, yet there was a noticeably slow development during his career. Horthy thought that the first Jewish law was appropriate, and he only considered the second Jewish law to be inhuman, but he did not detest it publicly and did not exercise his veto, even though there was no direct German pressure at the time.

There was a dispute between Szakály and Ungváry about Horthy’s role during the occupation: Szakály took the view that until June 1944, the governor was unaware of the fate of the Jews deported from Hungary, but then he stepped in and stopped further deportations. According to Ungváry, Horthy must have known much earlier what the Nazis’ intentions were with the Jews, and he describes several cases in which he had to have become aware of the Nazi plans.

There is also a debate between the two historians about how much Horthy had room to manoeuvre and about the number of Jews surviving the war relative to other occupied European countries. According to Szakály, it was in Hungary where most Jews remained, but Ungváry did not agree with him. The book concludes that Horthy would have had room for manoeuvre to confront the needs of the Germans even after the occupation. If Horthy had stepped in earlier, not only the Jews in Budapest could have been saved. Horthy failed both in political and moral terms, Ungváry concludes.

The author thinks his most important task is to reconstruct Horthy’s decision-making situations as accurately as possible, as he believes this has not been done thoroughly enough so far. Summarising Krisztián Ungváry, at the end of the book he concludes that not only Horthy’s anti-Semitism and behaviour during the deportations show his human and political incompetence, but also other elements of his work as governor. The discussion with Sándor Szakály also illustrated that these questions will divide Horthy’s image for a long time to come, but perhaps it will bring readers closer to thinking about what decisions Horthy made and how true the theory of a forced path is.

Source: 24.hu